Chinese Painting: A Glimpse into a Timeless Art

中國繪畫,一窺永恆的藝術

Chinese painting (guóhuà, 国画) stands among the world’s oldest and most enduring artistic traditions. Its origins reach back thousands of years, flourishing alongside poetry and calligraphy. Unlike Western art, which often pursues realism and linear perspective, Chinese painting strives to capture the qiyun (气韵) — the spirit, vitality, and inner essence of its subjects.

Rather than oil on canvas, traditional Chinese artists work with brushes, ink made from natural pigments, and water-based techniques on delicate paper or silk.

Styles and Forms

Chinese painting is broadly divided into two main approaches: Gongbi and Xieyi.

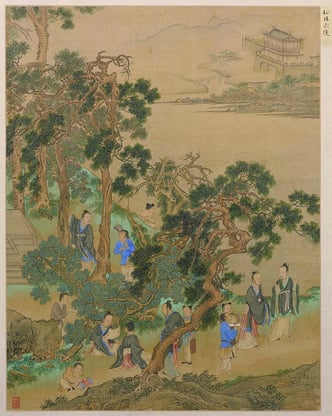

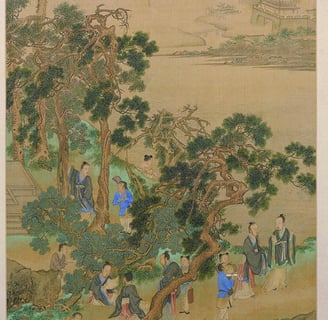

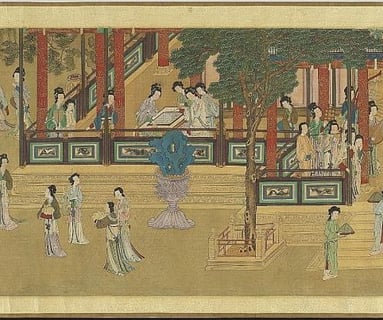

Gongbi (工笔) means “meticulous brushwork.” It is highly detailed, with fine lines and vivid colors, often used for portraits, narrative scenes, or intricate depictions of flowers and birds. Historically, this style flourished in the imperial courts.

Xieyi (写意), meaning “freehand” or “sketching ideas,” is also known as literati painting. It favors expressive, fluid strokes that reflect the artist’s inner state and spontaneous emotion, rather than precise realism. Often monochromatic, it turns subtle variations of black ink into a symphony of shades, evoking atmosphere and spirit rather than surface detail.

Themes

Classic subjects include landscapes (shanshui, 山水), flowers and birds (huaniao, 花鸟), and figures (renwu, 人物). These are more than mere depictions; each painting is an embodiment of the artist’s emotion, philosophy, and vision of harmony between humankind and nature. Throughout centuries, Chinese painting has evolved with dynasties and schools of thought, yet its distinct aesthetic remains remarkably consistent.

Figure Painting focuses on people, often depicting historical tales, mythology, or daily life. Early figure painting emphasized moral instruction, but later artists explored the subtle essence of human character and spirit.

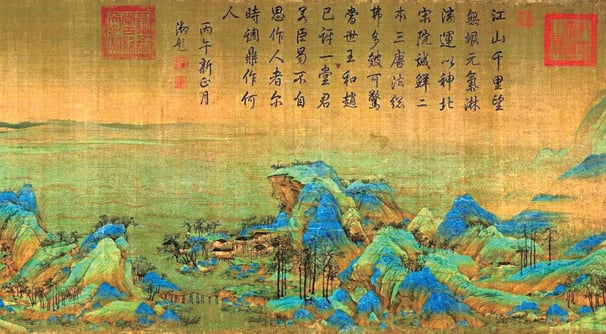

Landscape Painting is perhaps the highest form of Chinese painting. These works are not simply scenery but a spiritual journey through mountains and rivers, balancing the yin of water with the yang of rocks and peaks. Tiny human elements are often included to show our place within nature’s vastness.

Flower-and-Bird Painting features plants, animals, and seasonal symbols. These works often carry layers of meaning — plum blossoms for resilience, cranes for longevity, or bamboo for integrity.

”Six Hermits in the Pine Forest“ By Qiu, ying (1494-1552)

仇英 “松林六逸” Gongbi (工笔)

Philosophy

Rooted in Daoist, Confucian, and Buddhist thought, Chinese painting celebrates unity with nature, the balance of emptiness and form, and the idea that space left blank invites the viewer’s imagination to roam.

A single brushstroke may contain the wisdom of centuries — this is the enduring magic of Chinese painting.

Key Characteristics

Expressive Lines and Brushwork: The line is the lifeblood of Chinese painting — not only outlining form but also conveying emotion and energy. Every variation of thickness, dryness, or fluidity reveals the artist’s mastery and spirit.

The “Three Perfections”: A finished work often unites painting, poetry, and calligraphy, sometimes completed with the artist’s seal. This harmony of word, image, and brushwork reflects the painter’s mind and resonates with deep philosophical ideas.

Qiyun Shengdong (Spirit Resonance and Life Movement): One of the “Six Principles of Painting” formulated by Xie He in the 5th century, it refers to the vital force that animates a painting — a sense of life that flows through artist, brush, and subject.

Composition and Negative Space: The art of liubai (leaving blank) is integral to composition, creating balance and mood. Especially in landscapes, the goal is not exact depiction but evoking feeling and poetic atmosphere.

Symbolism: Many motifs carry symbolic meanings. Bamboo stands for resilience, plum blossoms for perseverance, and cranes for longevity, adding layers of cultural significance to the visual beauty.

Chinese painting is not merely an art form — it is a window into a worldview that treasures harmony, contemplation, and the endless dance between seen and unseen.

"Pure and Remote View of Streams and Mountains" By Xia, Gui (Song Dynasty)

夏圭 “溪山清遠圖“ landscapes (shanshui, 山水)

Painting and calligraphy share the same origin

書畫同源

It is widely believed that Chinese calligraphy and painting share a common origin, both evolving from the ancient practice of brushwork. Though they take different forms, they are deeply intertwined in spirit, technique, and philosophy.

Calligraphy and painting both emphasize the expressive potential of line, rhythm, and space. Painters, when portraying natural scenes such as the surging tides or the flowing rivers, strive to capture not only physical likeness but also the underlying spirit and vitality of nature. In parallel, calligraphers use strokes and composition to convey movement, energy, and emotion—often evoking the essence of flowing water without depicting it literally.

These two art forms also share common tools and materials—brush, ink, paper, and inkstone—and are often practiced side by side. Their artistic expressions reflect similar aesthetic values, such as balance, harmony, spontaneity, and inner meaning.

Together, calligraphy and painting represent two pillars of traditional Chinese art. They are not merely visual expressions but profound cultural practices that embody the philosophy, temperament, and worldview of Chinese literati. Through brush and ink, both arts seek to transcend surface appearances and reveal the deeper truths of life and nature

"Lady" By Pan, jiezi (1915-2002)

潘絜兹 ”仕女“ Gongbi (工笔)

"Lotus" By Xu, wei (1521-1593)

徐渭 ”荷花“ Xieyi (写意)

"Reciting Poems on Donkey's Back" By Xu, wei (1521-1593)

徐渭 ”驴背吟诗图“ Xieyi (写意)

Materials

The brush, ink, paper, and inkstone — known as the Four Treasures of the Study (文房四宝) — are the essential tools. Artists traditionally use black ink with delicate touches of color on silk or xuan paper, bringing life to landscapes, flowers, birds, and figures alike.

"Finches and Bamboo" By Emperor Huizong of Song,Zhao, ji (1082-1135)

宋徽宗趙佶“竹禽圖” Flowers and birds (huaniao, 花鸟)

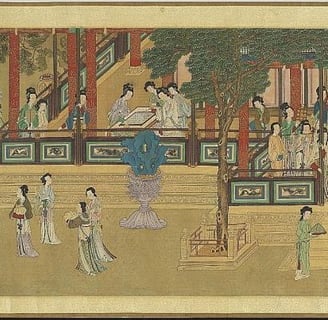

"Scroll of One Hundred Beauties" By Qiu, Ying (1494-1552)

仇英“百美圖卷” Figures (renwu, 人物)

"Facing the Moon“ Scroll By Ma, Yuan (1160-1225)