The Timeless Elegance of the Study Room and Its Treasures

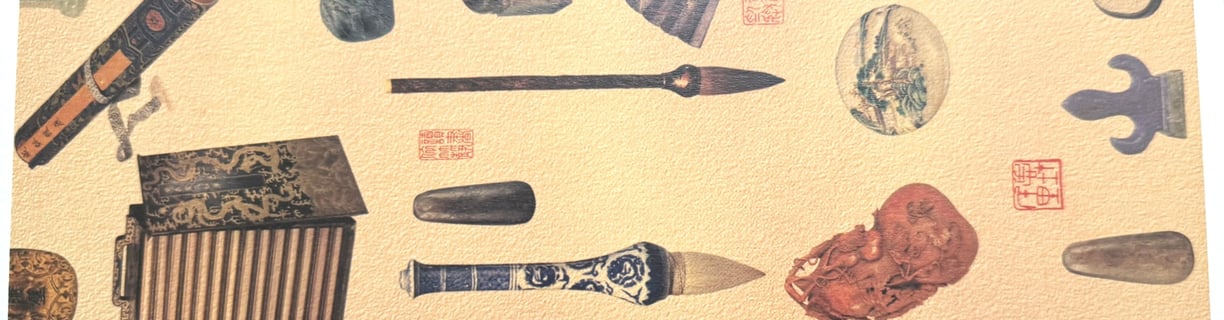

The "Four Treasures of the Study"—brush, ink, paper, and inkstone—are essential tools in traditional Chinese calligraphy and painting. But they are far more than just writing instruments.

In ancient China, a scholar’s study was much like a private library in a European noble’s home. It was a space not only for reading and writing, but also for composing literature, playing chess, appreciating antiques, and enjoying meaningful conversations with friends. The tools used in this space reflected the owner's taste, personality, and artistic sensibility.

The pursuit of elegance and refinement in these items gave rise to an aesthetic culture. These treasures came to symbolize the inner world of the scholar—calm, cultured, and deeply connected to the arts. It represents an extension of the scholar’s inner world. The Four Treasures of the Study are more than instruments, they are symbols of Chinese culture and aesthetics. For this reason, they were often called the "Four Friends of the Study" as well.

Each item embodies the skill of the artisan and the taste of its user. Over thousands of years, a wide array of supporting tools also emerged, including brush holders, ink beds, seal boxes, and paperweights. These items carry deep cultural significance, blending practical use with artistic value.

For generations, scholars used stationery not just for writing, but as a way to connect with the ideals and artistry of the past. They inscribed poetry, copied masterpieces, and infused their tools with literary allusions, turning everyday objects into expressions of personal philosophy and admiration for cultural heritage.

Over time, this refined way of life influenced broader Chinese culture, becoming an important part of the heritage of Chinese civilization.

Today, these treasures continue to inspire—offering a glimpse into the elegance, discipline, and enduring spirit of traditional Chinese culture.

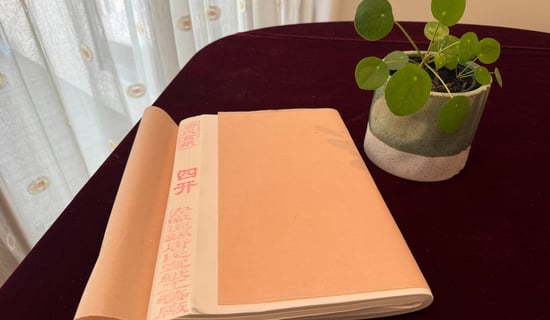

Paper: A Revolution of Communication

Long before paper, the Chinese wrote on bamboo slips, silk, and even bone. That changed with the invention of paper, traditionally credited to Cai Lun of the Eastern Han Dynasty (105 CE). But archaeological finds show that paper was in use even earlier, with examples from the Western Han Dynasty unearthed along the ancient Silk Road.

Early paper was made from natural fibers like bark, hemp, and old cloth. It was light, easy to write on, and easy to store—quickly replacing older materials.

By the Tang Dynasty, paper production had spread across China. The most famous is Xuan paper from modern-day Jing County, Anhui. Known as the “King of Paper,” it is prized for its softness, durability, and ability to absorb ink gracefully. Artists and calligraphers still treasure it today.

文房四寶

筆 · 墨 · 紙 · 硯

在中國傳統文化中,書房中不可或缺的四樣工具被稱為「文房四寶」——筆、墨、紙、硯。這四寶不僅是書寫與繪畫的基本工具,更凝聚了千百年的工藝、美學與人文精神。讓我們一起走進這些寶物背後的故事。

筆:士人的手之延伸

傳說中,秦朝大將軍蒙恬是毛筆的發明者,但考古發現顯示,早在兩千多年前的墓葬中,就已有與現代毛筆極為相似的筆具——竹桿、獸毛筆頭、並配有筆套以保護筆鋒。

毛筆的筆桿可用竹、象牙,甚至金銀製成;筆毫則採用羊毛、兔毛、黃鼠狼毛等不同材質。優秀的毛筆需具備四德:

尖(筆鋒銳利)

齊(筆毫整齊)

圓(筆腹飽滿)

健(彈性有力)

依用途不同,筆的形制與軟硬粗細各異。唐宋時期,安徽宣州的「紫毫筆」名聲遠播;而明清以降,浙江湖州則成為製筆重鎮,所產「湖筆」至今仍受書畫家珍愛。

毛筆不僅是工具,更是書畫家表現心意與風骨的媒介。由於筆會隨使用而耗損,能保存至今的古筆極為珍貴。

墨:煙火之中生藝術

在人工墨出現之前,中國古人曾使用天然顏料書寫,如彩陶上的繪畫、甲骨文、以及簡牘上的墨跡。後來,匠人開始以松煙或油煙混合膠料,壓模成形,製作出固體墨錠,最早可追溯至漢代。

製墨工藝極為講究。優質的墨質地細膩、色澤濃黑、香氣宜人且歷久不褪。墨模常刻有圖案與詩文,使墨本身成為藝術品。安徽徽州是中國古代重要的製墨中心,其中名匠胡開文所創之「徽墨」至今仍享盛名。

如今雖多用瓶裝液體墨水,但傳統墨錠仍以其儀式感與質量,受到書畫愛好者喜愛。

紙:文化傳播的大革命

在紙張出現之前,中國人書寫材料包括竹簡、絲帛與獸骨等。直到東漢時期(公元105年),蔡倫改良造紙術,推動了紙張的普及。不過,實際出土的早期紙張顯示,西漢時期已有紙的使用,絲綢之路沿線的古墓中便出現過早期紙品。

古紙以樹皮、麻、破布等纖維為原料,質輕、書寫方便,迅速取代了舊有材料。

唐代以後,造紙技術遍及全國,其中最著名的是來自安徽涇縣的宣紙。它被譽為「紙中之王」,柔韌耐久,吸墨適中,至今仍是書畫創作的首選。

硯:墨的誕生之地

硯台是製墨的起點——它將固體墨與水結合,磨製成可用的液態墨。雖看似簡單,其實硯的材質與設計對墨的品質有極大影響。

最早的硯可追溯至漢代,多為石製。後來,硯本身成為文人收藏與品賞之物。歷代名硯中最負盛名的有:

端硯(廣東):石質細潤如玉,溫潤可人

歙硯(安徽):紋理自然,磨感滑順

洮硯(甘肅):產自河床,稀少且具觀賞性

澄泥硯(山西):以河泥為原料,燒製而成,形制雅致

優良的硯台可使墨色均勻、濃淡自如,是書畫藝術的重要輔助者。

活的傳統

文房四寶孕育了中國古代的文學、思想與藝術。它們不只是工具,更是士人修身養性的象徵,亦為帝王珍藏、文人鑒賞、匠人世代傳承的文化遺產。

當您欣賞這些寶物時,不妨想像古代書生伏案而坐,研墨起筆、落紙傳情的情景。這四寶,不僅連結了手與心,更映照著中國文明的靈魂。

Brush

Brush: The Extension of the Scholar’s Hand

Legend credits General Meng Tian of the Qin Dynasty with inventing the brush, but archaeological finds tell a deeper story. Brushes dating back over 2,000 years have been found in ancient tombs—made from bamboo handles and animal hair, often capped for protection. These early tools were surprisingly similar to modern brushes.

Brushes came in many forms, with handles made of bamboo, ivory, or even gold, and tips crafted from goat, rabbit, or weasel hair. The best brushes share four qualities:

Sharp (a fine tip)

Neat (uniform hairs)

Round (a full body)

Strong (good resilience)

Different brushes suit different needs—some for bold strokes, others for delicate lines. During the Tang and Song dynasties, Xuanzhou in Anhui was famous for its “purple hair” brushes. Later, in the Ming and Qing dynasties, Huzhou in Zhejiang became the center of brush making, producing the exquisite “Hu brushes” still prized today.

Brushes are not just tools—they are expressions of the artist’s spirit. Because they wear out with use, ancient brushes are rare treasures today.

Inkstone: Where Ink Is Born

The inkstone is where the magic begins—a tool for grinding solid ink with water to create liquid ink. Though it may look simple, it is a finely crafted instrument, designed to hold water, grind soot, and bring out the best in ink.

Among all tools, the inkstone held a special place. It was cherished as a lifelong companion, As Chen Jiru wrote in the Ming Dynasty, The inkstone is to a scholar what a mirror is to a beauty; it is the most intimate thing in one’s life.” Inkstone appreciation became a refined art in itself, with famous figures like Mi Fu and Su Shi collecting, crafting, and writing about them. Their passion helped elevate the inkstone into a symbol of intellectual and artistic pursuit.

Some of the earliest inkstones date back to the Han Dynasty, carved from smooth stone. Over time, the inkstone itself became a collector’s item. The four most famous types are:

Duan Inkstone from Guangdong, prized for its jade-like smoothness.

She Inkstone from Anhui, known for its natural patterns and silky surface.

Tao Inkstone from Gansu, made from riverbed stone, rare and beautiful.

Chengni Inkstone from Shanxi, shaped from river mud and fired like pottery.

A good inkstone keeps the ink smooth, rich, and ready to bring brush and paper to life.

Ink: Where Smoke Becomes Art

Before artificial ink, early Chinese writing used natural pigments—seen on painted pottery, oracle bones, and ancient bamboo slips. Over time, artisans learned to make solid inksticks from the soot of pine or oil smoke, mixed with glue and pressed into molds. The earliest of these date back to the Han Dynasty (over 2,000 years ago).

Making ink was an art in itself. The best ink was smooth, rich black, long-lasting, and fragrant. Ink molds were often beautifully carved, turning a simple tool into a work of art. Some of the finest ink came from Huizhou in Anhui Province, where master craftsman Hu Kaiwen created what we now call “Hui Ink.”

Though most artists today use bottled ink, traditional hand-ground inksticks are still loved for their elegance and quality.

The Four Treasures of the Study

Brush · Ink · Paper · Inkstone

In traditional Chinese culture, the scholar’s desk was incomplete without the Four Treasures of the Study: the brush, ink, paper, and inkstone. Together, they formed the essential tools of calligraphy and painting, and each holds centuries of craftsmanship, artistry, and history. Let’s take a closer look at their stories.

A Living Legacy

Together, these four tools nurtured Chinese thought, literature, and visual art for centuries. They were not only used by scholars and poets but also revered by emperors, collected by connoisseurs, and refined by generations of craftspeople.

As you explore these treasures, imagine the scholar at his desk—grinding ink, choosing a brush, and setting his thoughts to paper. The Four Treasures are more than tools—they are a window into the soul of Chinese civilization.