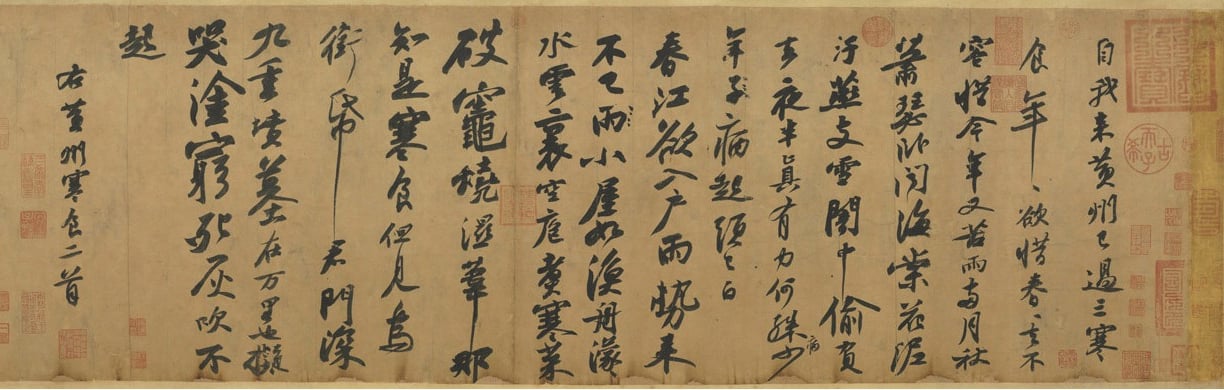

The Cold Food Poems by Su Shi: A Masterpiece of Chinese Literature and Calligraphy

Su Shi’s Cold Food Poems, written during his exile in Huangzhou, are widely regarded as a masterpiece of both Chinese literature and calligraphy. Composed during a time of profound personal and political turmoil, these poems reflect the deep emotional and philosophical transformation of one of China’s greatest cultural figures.

Historical Background

Su Shi (also known as Su Dongpo) was exiled to Huangzhou after opposing Wang Anshi’s political reforms. His dissent led to his removal from the capital, and later, to his involvement in the infamous “Crow Terrace Poetry Case,” which accused him of subversion through verse. Shortly after, he was banished to the remote region of Huangzhou.

By the third year of his exile, during the Cold Food Festival — a time traditionally reserved for mourning and remembrance — Su Shi found himself living in a humble dwelling, reflecting on his political downfall and personal misfortunes. Moved by the moment, he spontaneously picked up a brush and composed what would become the iconic Cold Food Poems, specifically the calligraphic work known as Han Shi Tie (寒食帖).

This piece was not a formal manuscript — it bears no signature or seal — but like Yan Zhenqing’s Draft of a Requiem to My Nephew, it was created impulsively, driven by raw emotion.

Poem I: A Meditation on Time and Decay

In the first poem, Su Shi laments the passage of time since his arrival in Huangzhou (modern-day Huanggang, Hubei), noting that spring returns year after year, yet always slips away too quickly. As the persistent spring rains fall and autumn’s desolation sets in, he is filled with melancholy. He is suddenly reminded of the crabapple blossoms — a metaphor for his own noble character — whose petals are now scattered in the muddy earth by the wind and rain. Unnoticed, time has stolen their beauty.

He compares himself to a sickly youth who, even after recovery, finds his hair turned white.

Interpretation:

The poem is a powerful reflection on the transience of life and the erosion of personal ambition. Su Shi mourns how time, like a cruel blade, has worn away his ideals. The bleak imagery of "bitter rain" and "desolate autumn" evokes his sense of helplessness, likening himself to the crabapple flower — beautiful, noble, but now fading in a hostile political climate. Even if he were to rise again, he fears he would do so aged and worn, his youthful dreams long gone.

Poem II: Despair and Exile

In the second poem, Su Shi describes the torrential rain threatening to flood his home, which seems no sturdier than a fishing boat drifting through rivers and mist. His kitchen is bare, holding only a few winter vegetables, and his firewood is too damp to burn. There’s no sign that today is the Cold Food Festival — only crows carrying ghost money in their beaks. He reflects on the vast distance between himself and the imperial court, as well as his ancestral tombs. Like Ruan Ji, the disillusioned poet of old, he breaks down in tears, recognizing that ashes cannot be rekindled.

Interpretation:

This poem emphasizes Su Shi’s sense of hopelessness. He is at rock bottom, his career in ruins. The heavy rain mirrors his desolate situation, while the broken, drifting house becomes a metaphor for his life’s directionless wandering. In poverty and isolation, he still clings to hope — trying to light a fire with wet reeds — a symbol of futile optimism. The thought of his distant homeland and court brings only more grief. Cut off from everything he held dear, Su Shi feels forgotten by the world, overwhelmed by sorrow.

Emotional and Philosophical Depth

Together, these two poems express a profound sense of sorrow and disillusionment. They mark a pivotal moment in Su Shi’s life, when his youthful political ambitions had fully unraveled, forcing him into a life of hardship, introspection, and creative rebirth. The Cold Food Festival — a day for mourning and remembrance — naturally intensifies the poems’ nostalgic and melancholic tone.

Themes of loss, exile, and spiritual solitude pervade the verses. Yet, despite the despair, Su Shi’s emotional journey is not devoid of resilience. His tone shifts between bitterness and humor, sorrow and serenity, as he explores fate, identity, and the fleeting nature of life.

A standout line —

“The spring river wants to enter my door; the rain keeps coming without end.”

— illustrates the uncontrollable forces of nature and destiny, serving as a poignant metaphor for political persecution and inner helplessness.

Calligraphy as Emotional Expression

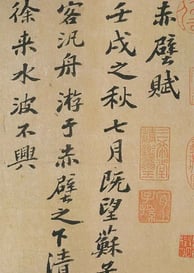

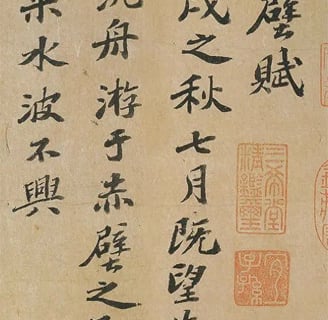

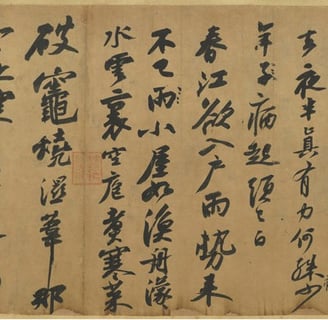

Han Shi Tie is celebrated not only for its poetic content but also for its brilliance as a work of calligraphy. It is considered one of the greatest examples of Chinese running script (行书) in history — a spontaneous, visually dynamic expression of the poet’s emotional world.

Why the Calligraphy Is Extraordinary:

Rhythmic Variation: The flow and pacing of the brushwork rise and fall with the emotion of the text — energetic in anger, gentle in reflection. The changing tempo gives life to the poem on the page.

Spontaneity with Control: The strokes are fluid and natural, yet never chaotic — showing Su Shi’s technical mastery and internal balance.

Unity of Form and Feeling: The emotional shifts in the poem are mirrored visually — bold, rough lines in moments of intensity, and light, delicate strokes during quiet introspection.

Historical Significance: As one of the few surviving authentic works by Su Shi, this manuscript holds immense cultural and aesthetic value.

Modern calligraphers and scholars continue to praise Han Shi Tie for achieving what they call the “unity of brush and spirit” — where one can “read” the poet’s emotions through the energy of the strokes alone.

A Synthesis of Literature, Art, and Emotion

The Cold Food Poems, especially Han Shi Tie, represent the peak of Su Shi’s literary and artistic expression. Created during a time of crisis and transformation, they exemplify the resilience of the human spirit and the enduring power of creativity in the face of suffering.

They are more than poems, more than calligraphy — they are living testaments to a man who turned exile into enlightenment, sorrow into beauty.

Through the seamless fusion of emotion, poetry, and brushwork, Han Shi Tie stands as a timeless work of art — a voice from a thousand years ago that still speaks to us today.

Su, Shi (Su, Dongpo ) 蘇軾 (蘇東坡)

( 1037-1101)

Su Shi (1037–1101), also known by his pen name Su Dongpo, was one of the most celebrated figures of the Song dynasty and a towering polymath in Chinese cultural history. A gifted poet, essayist, calligrapher, painter, and statesman, Su Shi's literary brilliance and artistic legacy have made him a lasting symbol of Chinese intellectual and artistic achievement.

Born in Meishan, Sichuan Province, into a scholarly family, Su Shi excelled in the imperial civil service examinations at a young age, earning top honors. His early promise brought him into the court bureaucracy, where he served in various official positions across the empire. However, his forthright political views and reformist stance, often at odds with the dominant New Policies faction led by Wang Anshi, led to repeated political conflicts and periods of exile.

Despite his turbulent political career, Su Shi's literary achievements flourished throughout his life. He was a master of multiple literary forms, including shi poetry, ci lyrics, prose essays, and fu rhapsodies. His writing is characterized by bold imagination, rich emotion, philosophical depth, and a balance of elegance and spontaneity. Whether reflecting on nature, friendship, wine, exile, or Buddhist and Daoist thought, Su Shi infused his works with a distinctive personal voice that was at once refined and accessible.

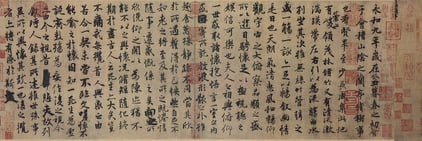

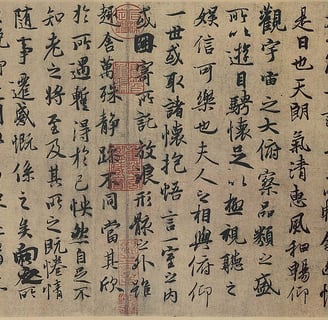

Among his best-known poems are “Red Cliffs” (赤壁賦) and its sequel, composed during his exile in Huangzhou. These meditative pieces combine lyrical description, historical reflection, and personal introspection, and are considered masterpieces of Song prose and poetry. His ci poetry, which was traditionally used for love lyrics, was elevated by Su Shi to encompass broader themes like politics, nature, and philosophy. His famous ci, such as “Prelude to the Water Melody” (水調歌頭), are celebrated for their grandeur and emotional resonance.

Su Shi was also a highly skilled calligrapher, whose style was bold, free, and deeply expressive. Along with Cai Xiang, Huang Tingjian, and Mi Fu, he is regarded as one of the “Four Great Calligraphers of the Song Dynasty.” He absorbed the techniques of earlier masters like Wang Xizhi and Yan Zhenqing but developed a personal style that emphasized natural flow over rigid formality. His calligraphy, often written in semi-cursive and cursive scripts, conveyed a sense of ease and inner strength that paralleled his literary voice.

In visual art, Su Shi was one of the earliest advocates of the literati painting tradition, which emphasized personal expression and brushwork over realism. Although few of his paintings survive, his theoretical writings on art profoundly influenced Chinese aesthetics, helping to shape the cultural ideal of the scholar-artist.

Su Shi's life was marked by ups and downs—exile, political rivalry, and personal loss—but he maintained an enduring optimism and a sense of detachment shaped by Buddhist and Daoist thought. His intellectual breadth, humanistic spirit, and creative vitality made him a central figure in Chinese cultural history.

Today, Su Shi is remembered not only as a literary genius but also as a symbol of artistic freedom, resilience, and moral integrity. His works remain widely read and admired, and his influence continues to shape Chinese literature, calligraphy, and art.

寒食詩 蘇軾

自我來黃州。已過三寒食。年年欲惜春。春去不容惜。

今年又苦雨。兩月秋蕭瑟。臥聞海棠花。泥污燕支雪。

闇中偷負去。夜半真有力。何殊病少年。病起頭已白。

春江欲入戶。雨勢來不已。小屋如漁舟。濛濛水雲裡。

空庖煮寒菜。破竈燒濕葦。那知是寒食。但見烏銜帋。

君門深九重。墳墓在万里。也擬哭塗窮。死灰吹不起。

右黃州寒食二首。

Two Poems on Cold Food Festival at Huangzhou (黃州寒食二首)

Su Shi (Su Dongpo)

Since I came to Huangzhou,

Three Cold Food Days have passed.

Each year I wish to cherish spring,

But spring slips away before it can be cherished.

This year, bitter rain—

Two months of autumn’s chill in spring.

Lying down, I hear the crabapple bloom,

Soiled by mud, like rouge on melting snow.

In the dark, it’s stolen away,

Midnight’s strength is true.

What difference from a sickly youth?

Rising from illness, my hair already white.

The spring river wants to enter my door,

The rain falls on and on.

My small hut is like a fishing boat,

Floating in mist and watery clouds.

The cold kitchen cooks bitter greens,

The broken stove burns damp reeds.

How would I know it is Cold Food Day?

Only black crows carry paper in their beaks.

The palace gates stand deep—ninefold walls,

While graves lie ten thousand miles away.

I, too, would cry at the road’s end,

But dead ashes stir no more in the wind.