This work tells an ancient, elegant story.

On March 3rd, 353 AD, in the late spring, Wang Xizhi (303-361 CE), then the governor of Kuaiji County, hosted a gathering of over 40 scholars and refined gentlemen at the Orchid Pavilion (Lanting) in Shanyin. It was more than a social event with food and wine—it was an elegant literati activity. The guests played a poetic game called Qushui Liushang. Seated along a winding stream, they floated wine cups downstream. Sometimes, the cups would be slowed or stopped by twists in the current, stones, or overhanging branches. When a cup came to a stop in front of someone, that person had to compose a poem—or else drink. By the end, 37 poems had been written, and the group decided to compile them into a collection. Naturally, a preface was needed—and the honor of writing it fell to Wang Xizhi.

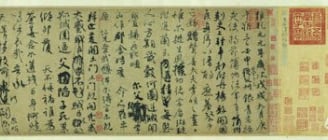

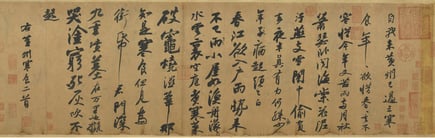

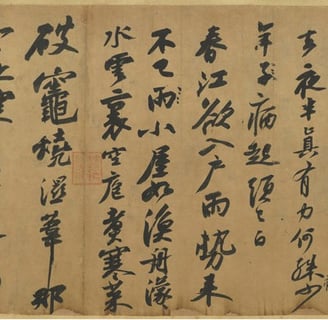

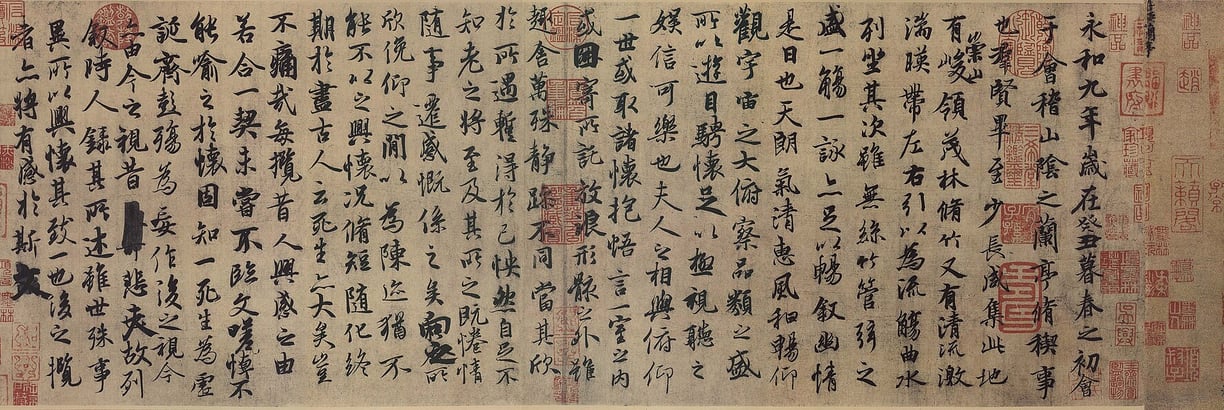

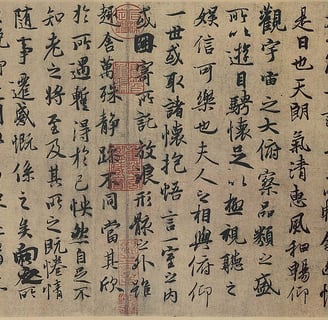

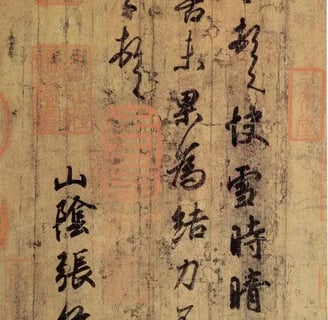

Having had a few cups of wine, Wang sat down, reflected for a moment, and wrote this preface. This is the very piece you see before you, later known as the "Preface to the Poems Collected from the Orchid Pavilion" (Lantingji Xu). It is a masterpiece of both literature and calligraphy—widely memorized by generations of scholars and admired as the finest example of running script (xingshu). Of course, the original no longer exists—after all, more than 1,600 years have passed, during which China endured countless wars and dynastic changes. What you're viewing now is a faithful Tang Dynasty reproduction, created by a court calligrapher using the double hook outline filling* technique to preserve Wang Xizhi’s original brushwork. It is said that the true original was buried with Emperor Taizong (598-649 CE) of Tang.

*Double Hook Outline Filling is a traditional technique used in East Asian calligraphy and painting. It involves outlining the shape of an object or character with fine ink lines, a process commonly known as "hooking." The term "double hook" refers to the method of drawing two parallel lines—usually from left to right or from top to bottom—around the contours of the subject. In the context of calligraphy, it is used to trace and reproduce ancient scripts. Artists apply thin and strong ink lines along both sides of each character's original strokes, effectively capturing their form. This outlining process is called "double hook," and when ink is added within the outlines to complete the image or characters, it is known as "double hook outline filling" (双钩填墨).

The following is the English translation of "Lanting Collection Preface".

Wang, xizhi 王羲之(266-420)

Wang,Xizhi: The Sage of Calligraphy

Wang Xizhi, born in Shanyin (now Shaoxing, Zhejiang) during the Eastern Jin Dynasty, came from a prominent family deeply rooted in scholarship and calligraphy. His father, Wang Kuang, was a governor and an accomplished calligrapher, and the cultural traditions of the Wang family provided Wang Xizhi with a rich foundation. From a young age, he received rigorous education, studied the classics, and practiced calligraphy by copying ancient steles and rubbings.

The Eastern Jin period, though politically fragile due to northern invasions and the fall of the Western Jin, saw a flourishing of arts in the south as gentry migrated and brought Central Plains culture with them. This environment fostered an elegant, refined lifestyle that greatly influenced Wang Xizhi, who, despite holding official posts, chose to live in seclusion and focus on artistic pursuits rather than political ambitions.

Wang’s calligraphy was shaped by several factors:

Family background gave him early access to fine works and artistic inspiration.

Gentry lifestyle emphasized cultured living, where calligraphy was a noble pursuit.

Political instability encouraged spiritual retreat and self-expression through art.

Religious influence, particularly Taoism, inspired the natural, flowing style found in his work, reflecting the idea of “ruling by inaction.”

His signature style emerged primarily in running script (xingshu), praised for its smooth, natural rhythm and balanced structure. His most famous work, the Lanting Preface, is considered the pinnacle of running script art. Its flowing lines and expressive strokes resemble a landscape painting, with perfect harmony between form and movement.

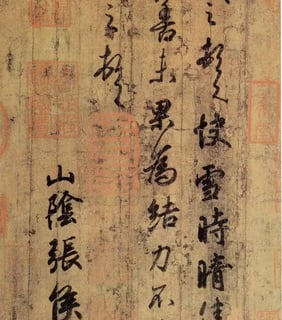

Wang Xizhi also excelled in cursive script (caoshu), known for its wild yet controlled energy. Works like Chu Yue Tie and Shi Qi Tie show how he infused cursive writing with structure, making it both expressive and readable. In regular script (kaishu), he achieved precision without rigidity, creating upright yet lively characters, as seen in On Yue Yi. Across all styles, his writing combined elegance, discipline, and innovation.

Wang Xizhi’s legacy is vast. Dubbed the “Sage of Calligraphy,” he not only elevated the status of running script but also set the aesthetic benchmark for future generations. His concept of “spirit and vitality” in brushwork became central to Chinese calligraphic art. His influence extended to his son Wang Xianzhi, forming the famed “Two Wangs” style.

Later masters like Yan Zhenqing, Ouyang Xun, and Su Shi, as well as Ming and Qing figures like Zhao Mengfu and Dong Qichang, all studied and evolved Wang's techniques. His impact reached beyond China, notably influencing Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese calligraphy. In Japan, he is revered as the “Pen Saint.”

In summary, Wang Xizhi’s unique blend of artistry and personal philosophy shaped the course of Chinese calligraphy. His work remains a timeless model of aesthetic and expressive excellence, with his influence enduring across centuries and cultures.

Lanting Collection Preface (Lantingji Xu)

Wang, xizhi

In the ninth year of the reign Yungho [353 CE], Kueichou in cycle, we met in late spring at the Lanting in Shanyin to hold the purification ceremony.

All the worthy have arrived, and people both young and old are gathered.

All In the background lie high peaks and deep forests, while a clear, gurgling brook catches the light to the right and to the left.

We used the stream as a winding stream for the wine cups, and sat in a row beside the winding stream. Although there was no grand occasion of playing music, drinking a little wine and writing a little poetry were enough to express the deep and hidden feelings.

It is a clear spring day with a mild, caressing breeze, the vast universe, throbbing with life, lies spread before us, entertaining the eye and pleasing the spirit and all the senses. It is perfect.

Now when men come together, they let their thoughts travel to the present. Some enjoy a quiet conversation indoors and others play about outdoors, occupied with what they love.

Although we select our pleasures according to our inclinations—some noisy and rowdy, and others quiet and sedate—yet when we have found that which pleases us, we are all happy and contented, to the extent of forgetting that we are growing old. And then, when satiety follows satisfaction, and with the change of circumstances, change also our whims and desires, there then arises a feeling of poignant regret.

In the twinkling of an eye, the objects of our former pleasures have become things of the past, still compelling in us moods of regretful memory. Furthermore, although our lives may be long or short, eventually we all end in nothingness. “Great indeed are life and death”, said the ancients. Ah! What sadness!

I often study the joys and regrets of the ancient people, and as I lean over their writings and see that they were moved exactly as ourselves, I am often overcome by a feeling of sadness and compassion, and would like to make those things clear to me

ell I know it is a lie to say that life and death are the same thing, and that longevity and early death make no difference!

Alas! The people of the future will look upon us as we look upon those who have gone before us.

Hence I have recorded here those present and what they said. Ages may pass and times may change, but the human sentiments will be the same;

know that future readers who set their eyes upon these words will be affected in the same way.

蘭亭集序

王羲之

永和九年,歲在癸醜,暮春之初,會於會稽山陰之蘭亭,修禊事也。群賢畢至,少長咸集。此地有崇山峻嶺,茂林修竹,又有清流激湍,映帶左右。引以爲流觴曲水,列坐其次。雖無絲竹管絃之盛,一觴一詠,亦足以暢敘幽情。

是日也,天朗氣清,惠風和暢。仰觀宇宙之大,俯察品類之盛,所以遊目騁懷,足以極視聽之娛,信可樂也。

夫人之相與,俯仰一世。或取諸懷抱,悟言一室之內;或因寄所托,放浪形骸之外。雖趣捨萬殊,靜躁不同,當其欣於所遇,暫得於己, 快(怏)然自足,不知老之將至。及其所之既倦,情隨事遷,感慨繫之矣。向之所欣,俯仰之間,已爲陳跡,猶不能不以之興懷。況修短隨化,終期於儘。古人雲:“死生亦大矣!”豈不痛哉!

每覽昔人興感之由,若合一契,未嚐不臨文嗟悼,不能喻之於懷。固知一死生爲虛誕,齊彭殤爲妄作。後之視今,亦猶今之視昔,悲夫!故列敘時人,錄其所述。雖世殊事異,所以興懷,其緻一也。後之覽者,亦將有感於斯文。

Qushuiliushang 曲水流觞图 山本若麟 Yamamoto Jakurin - 『隠元禅師と黄檗宗の絵画展』 神戸市立博物館

Lanting today (Orchid Pavilion today)