Appreciating Chinese Calligraphy: A Visual and Spiritual Art

Chinese calligraphy is more than just writing or brushwork—it’s a deeply expressive visual art form rooted in centuries of philosophy, aesthetics, and culture. Even if you don’t read Chinese characters, you can still enjoy the artistic beauty of calligraphy, much like appreciating abstract painting or instrumental music.

1. Calligraphy as Visual Art

If you’re unfamiliar with Chinese characters, begin by treating calligraphy as a visual experience.

See It as a Static Painting

Start by observing the work as a whole:

Is it composed of single characters or many? A few lines or an entire composition?

Are the characters neat and evenly spaced, or varied in size and rhythm, flowing like musical notes?

Pay attention to composition, balance, and how the characters interact with blank space. The white space is just as important—it creates rhythm and breath, like in abstra

Imagine It as a Moving Process

Now picture the piece not as a finished image, but as a performance:

Imagine the artist starting from a blank sheet—grinding ink, moistening the brush, choosing their words.

Observe the brushstrokes: Are they thick or thin? Fast or slow? Controlled or spontaneous?

Notice how the ink varies in intensity—dark and bold in places, light and delicate in others.

Look at how the characters are spaced and arranged: Is there harmony, contrast, or dynamic tension?

Don’t miss the subtle details: the tone of the paper, the red seal stamps, or the signature placement.

Calligraphy can be like a dance frozen in time, where each stroke reveals movement, energy, and intention.

2. Understanding the Calligraphic Styles

Chinese calligraphy has evolved over thousands of years through a variety of script styles. Each has a unique visual rhythm and reflects a different historical and artistic context. Appreciating these styles is like recognizing different genres in music—each has its own tempo, emotion, and flavor.

- Oracle Bone Script (甲骨文): The earliest known Chinese writing—pictographic, carved into bone or turtle shells, irregular in form.

- Seal Script (篆书): From the Qin and Han dynasties (over 2,000 years ago), known for its even lines, tall structures, and symmetry.

- Clerical Script (隶书): With broad, flat characters and wave-like strokes, it marked a shift toward efficiency and artistic stylization.

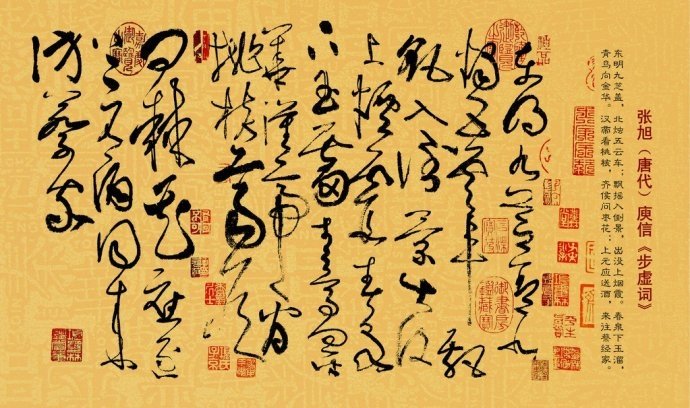

- Cursive Script (草书): Fast, flowing, often abstract—expressing strong emotion and movement.

- Running Script (行书): A dynamic blend of cursive and regular styles—fluid, graceful, and versatile.

- Regular Script (楷书): The most balanced and legible, ideal for learning, characterized by straight strokes and orderly structure.

3. Beyond the Surface: Emotion and Spirit

As you become more familiar, you can begin to sense the emotional and spiritual energy behind the work.

Observe the rhythm of the brush—its speed, pressure, and pauses.

Feel the qi yun (气韵), the “spiritual resonance” or dynamic life force that breathes through the strokes.

Try to sense the artist’s emotional state: were they calm, joyful, angry, anxious, restrained, or wild?

Calligraphy is not just about form—it’s a powerful form of self-expression, much like painting or music.

4. The Context Enriches the Experience

To deepen your understanding, explore the context behind the work:

Who was the artist? What era did they live in? What philosophies or traditions shaped their work?

Did they write poetry or famous sayings? Were they scholars, monks, officials?

Who influenced their style? What materials did they use?

These insights add layers of meaning to the piece.

5. Seek Translation or Interpretation

If you’re in a gallery or museum, check for descriptive labels. Online, take a photo and ask for a translation or interpretation (you can even ask me!).

Understanding the words often reveals profound messages—philosophy, poetry, personal reflection—adding emotional and intellectual depth.

6. A Final Thought

Chinese calligraphy began as writing but became so much more. Influenced by a deep reverence for nature and the idea of harmony between humanity and the universe, it evolved into a unique art form. Unlike many writing systems that are only practical or decorative, Chinese characters emerged from observation and imitation of nature.

As Tang dynasty calligrapher Zhang Huai-Guan once said:

“Writing expresses thought, and calligraphy seeks to align with the Dao—the natural, harmonious way of the universe.”

So even if you don’t read Chinese, through calligraphy you can experience beauty, rhythm, and spirit—and feel the brush of history and humanity.

Below, we present three masterpieces from the history of Chinese calligraphy, along with background information on their authors, the context in which they were written, and the central themes of each work—to serve as a guide for your appreciation. These works are Wang Xizhi’s Lanting Preface, Yan Zhenqing’s Sacrificial Essay for Nephew, and Su Shi’s Cold Food Poems—widely regarded as the first, second, and third greatest examples of running script in Chinese history. This ordering is not a comparison of their writing techniques; each work is outstanding and possesses its own unique character. Rather, the arrangement follows the chronological order in which they were created.

- It is important to note that these pieces were not created as intentional works of calligraphy. Rather, they are surviving manuscripts written naturally, without the authors aiming to produce polished calligraphic pieces. However, because of their exceptional skill and the particular emotional and situational contexts in which they wrote, these works became masterpieces. The mood, mindset, and thoughts of the authors are subtly embedded in the writing itself—an aspect that deserves special attention when viewing and appreciating these works.

Wang, Xizhi’s “Lanting Preface”

Yan, Zhenqing’s “Memorial to My Nephew”

Su, Shi ( Su Dongpo)’s “Cold Food Poems”