Chinese calligraphy is an ancient and revered art form that transcends mere communication, deeply embedding itself in Chinese culture as a supreme visual art, a channel for self-expression, and a reflection of philosophical and moral values.

The brief history

The history of Chinese calligraphy is not merely the story of writing—it is a vivid record of the rise of Chinese civilization itself. From the earliest oracle bone inscriptions to the flowing elegance of running script, each transformation in script style reflects both the practical needs and shifting aesthetics of the society that created it.

The roots of Chinese calligraphy stretch back over three millennia:

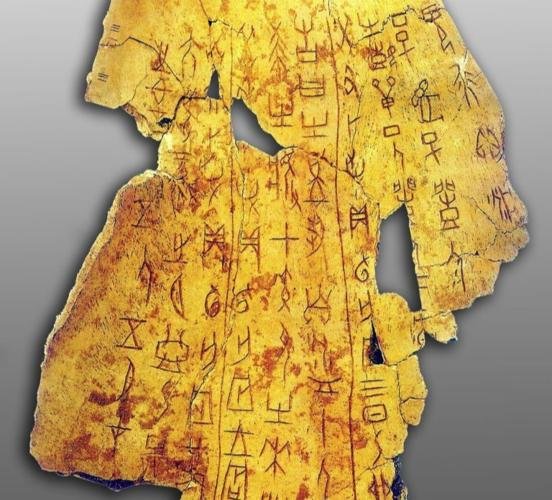

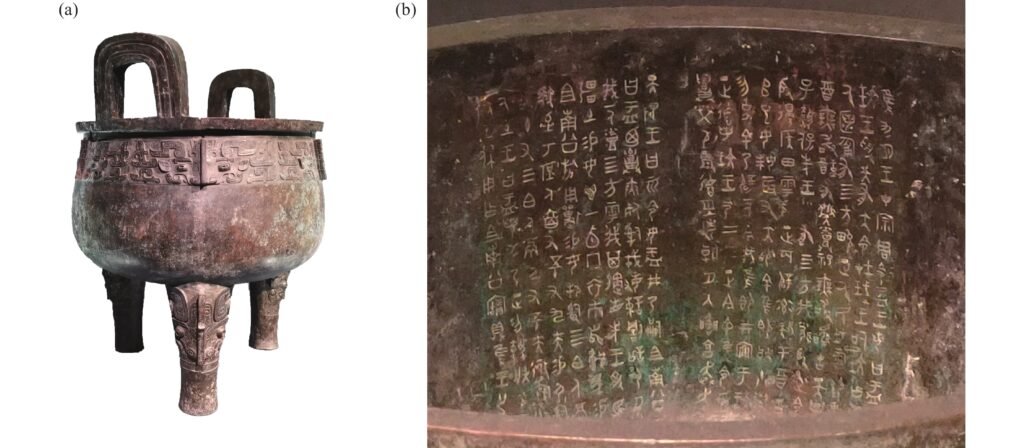

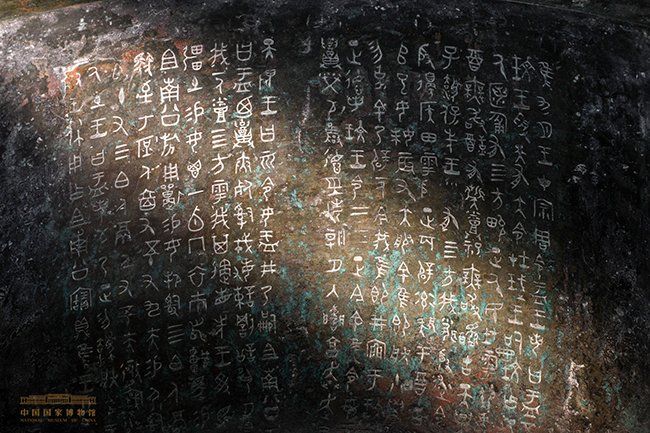

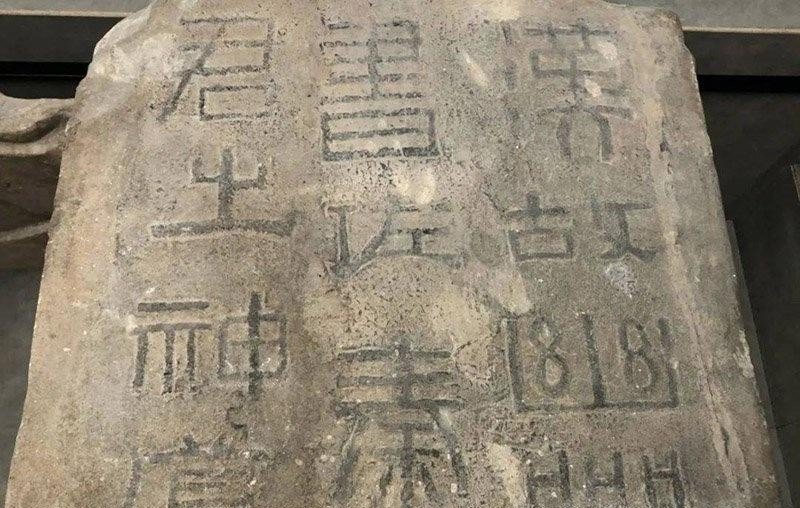

Shang Dynasty (c. 1600-1100 BCE): The earliest surviving Chinese scripts are found on oracle bones (animal bones and turtle shells) and bronze vessels. These early inscriptions, known as jiaguwen (oracle bone script), were primarily used for divination rituals. While lacking the linear variation of later calligraphy, they laid the foundation for the written language. Bronze inscriptions began to appear in the middle of the Shang Dynasty, and they were greatly developed in the later Zhou Dynasty.

Zhou Dynasty (1046 BC—256 BC): This period saw the widespread use of bronze inscriptions, also known as jinwen (金文), or bell and tripod (钟鼎文)inscriptions. These characters were cast onto bronze vessels primarily used in rituals, the issuance of royal decrees, military campaigns, hunting activities, and legal agreements. Bronze inscriptions from the Western Zhou era include references to nearly every Zhou king and provide valuable records of social, political, and ceremonial life, particularly the roles and actions of princes and nobles. During this period, brushes and ink began to become the main writing tools, marking the initial development of the art form of calligraphy.

Qin Dynasty (221-206 BCE): Before the unification of China by Qin Shihuang, the region was primarily divided among seven major vassal states: Qi, Chu, Yan, Han, Zhao, Wei, and Qin. Although these states were originally under the authority of the Zhou royal family, the gradual decline of Zhou power led each to become increasingly autonomous. During this period of political fragmentation, each state developed its own variant of written script. Influenced by geographical and cultural factors, the writing systems of these states diverged significantly, resulting in distinct regional styles. The phrase “the six states had different scripts, and writing was not unified” reflects this reality—each state used its own characters, and in some cases, multiple writing styles coexisted within a single state. This lack of standardization hindered effective governance and posed challenges to communication and cultural exchange across regions. After unifying China, Emperor Qin Shihuang standardized Chinese characters. His prime minister, Li Si, established the seal script (zhuan shu), a formal and structured style primarily used for official documents and seals.

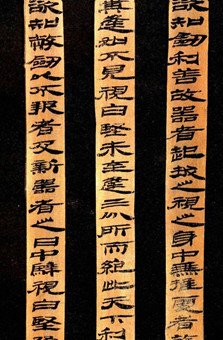

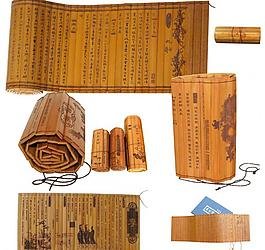

Han Dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE): This era was pivotal for calligraphy. Chinese artisans perfected the “Four Treasures of the Study” – brush, ink, paper, and inkstone – which remain the essential tools of calligraphers today. The clerical script (li shu) emerged, a more legible and widely adopted style for record-keeping. The regular script (kai shu), also known as zhen shu or zheng shu, also began to develop, which is still the basis for modern Chinese writing.

Post-Han Developments: Over subsequent centuries, further scripts evolved:

Running script (xing shu): A semi-cursive style that allows for more fluidity and connection between characters.

Cursive script (cao shu): Also known as “grass script,” this highly expressive and abstract style emphasizes rapid, continuous movement and often flows with separate characters merging into a continuous movement.

Many renowned calligraphers emerged, such as Wang Xizhi (c. 303 – c. 365 CE), often considered the most revered Chinese calligrapher. His work, though mostly known through copies, set high standards for technical skill and aesthetic beauty.

Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE): This period is often considered the “golden age” of Chinese calligraphy, with masters like Yan Zhenqing further developing the art form. It became mandatory for civil service examination candidates to be proficient in regular script, highlighting its importance in society.

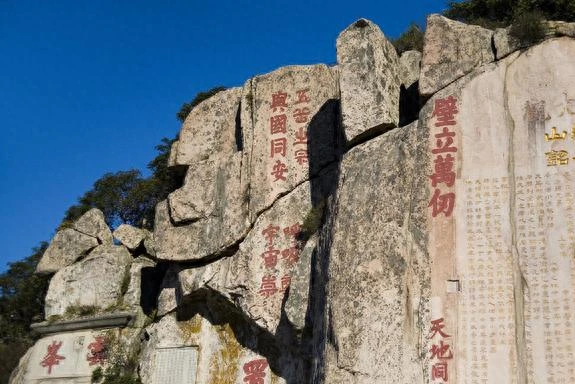

Later Dynasties and Modern Times: Calligraphy continued to evolve and be practiced by scholars, artists, and monks, often appearing on paintings to describe and explain the artwork, or to record details of its creation. Even in the 20th and 21st centuries, calligraphy remains central to Chinese art, finding new expressions in a globalized art world.